Ascending Aortic Aneurysm: Repair, Surgery, and Size Criteria

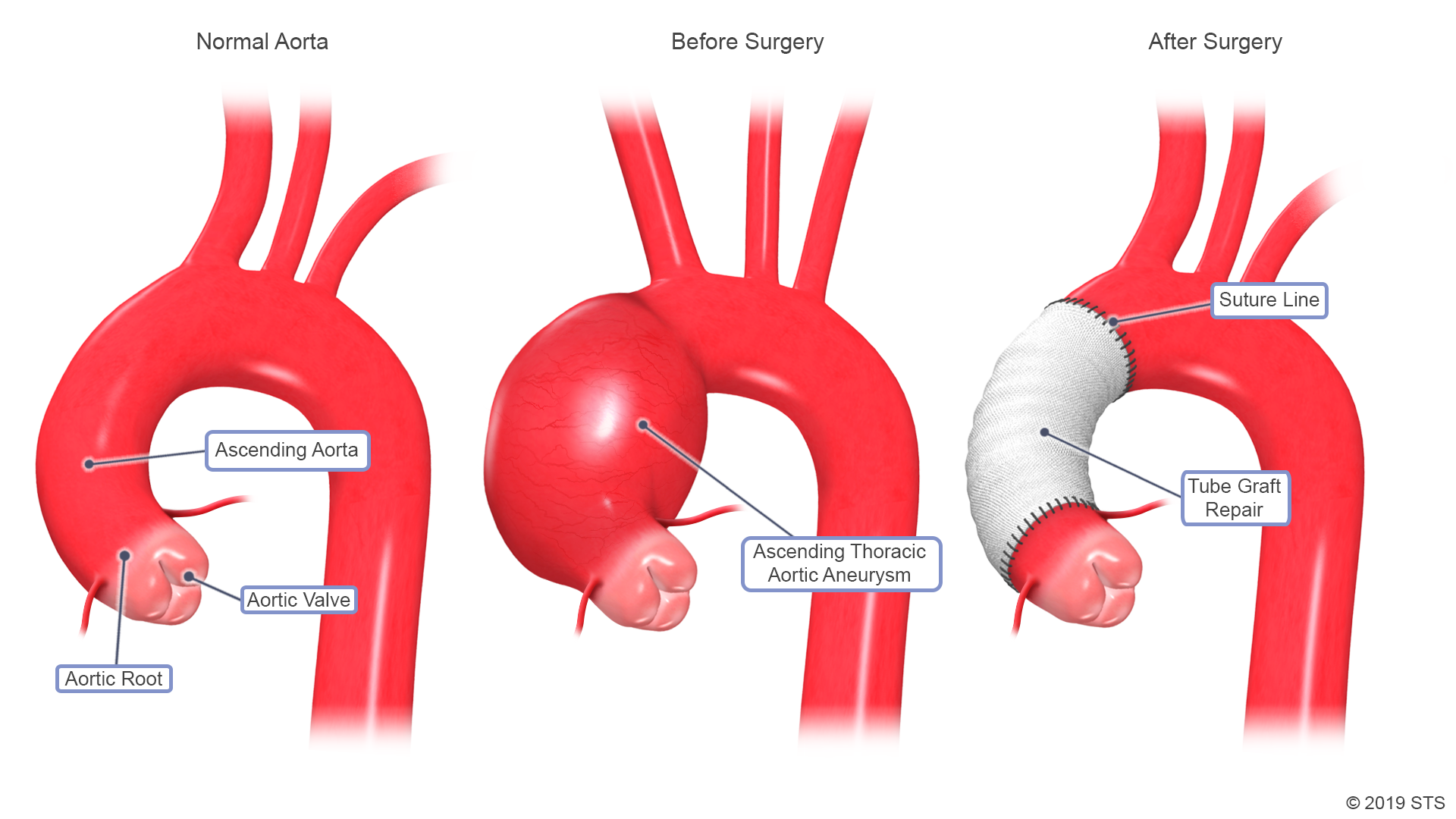

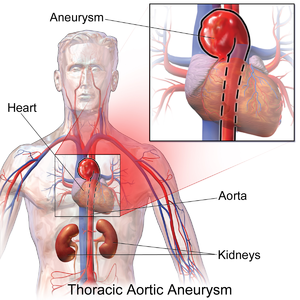

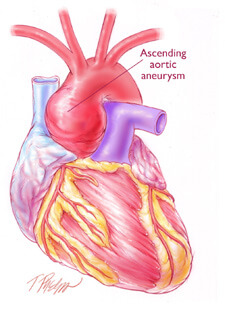

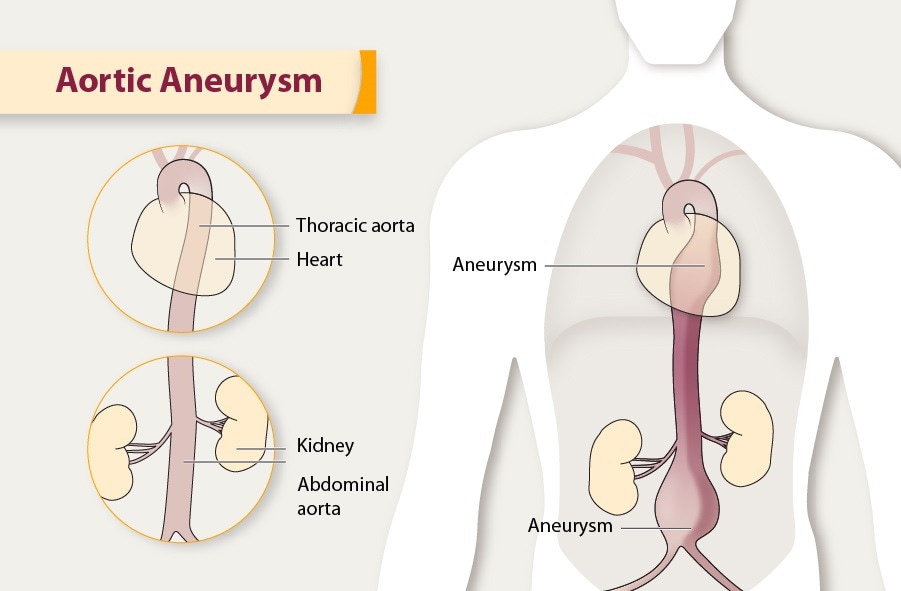

Ascending Aortic Aneurysm: Repair, Surgery, and Size CriteriaWarning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. Life expectancy after surgery to promote aortic aneurysmDaniel Hernández-Vaquero1Cardiac University of Asturias, University of Asturias, 33011 Oviedo, Spain; (J.S.); (A.E.); (C.M.); (R.D.)2Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias, 33011 Oviedo, Spain; (P.A); (P.); (P.); (P. Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria del Principado de Asturias, 33011 Oviedo, España; (P.A.); (C.M.); (I.P.)4Departamento de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, 33011 Oviedo, Spain5Departamento de Medicina, Universidad de Oviedo, 33011 Oviedo, España DataAbstractIntroduction: The hope of ancession is unknown. The life expectancy of a population depends on a collection of environmental and socio-economic factors in the territory where they reside. Our objective was to compare the life expectancy of patients under surgery to ascend aortic aneurysm with that of the general population that coincided with age, sex and territory. In addition, we seek to know late complications, causes of death and risk factors. Methods: All patients who replaced the ascending aortic aneurysm were included in our institution between 2000 and 2019. The long-term survival of the sample was compared with that of the general population using data from the National Statistical Institute. Results: For patients who survived the post-operative period, the survival accumulated to three, five and eight years was 94.07 per cent (IC95% 91.87–95.70 per cent), 89.96 per cent (CI 95 per cent 86.92–92.33 per cent) and 82.72 per cent (95% CI 77. 68–86.71 per cent). The cumulative survival of the general population in three, five and eight years was 93.22%, 88.30% and 80.27%. Cancer and heart failure were the main causes of death. Conclusions: The long-term survival of patients undergoing elective surgery for the ascending aortic aneurysm that survive the postoperative period fully recover their life expectancy.1. Introduction After atherosclerosis, aneurysm is the second most common disease of aorta []. The current incidence of aortic aneurysm is approximately 8 in 100,000 patients per year []. Several environmental and genetic risk factors have been identified in their formation []. Once a segment of the aorta is aneurysm, the entire aorta is considered pathological []. Due to the risk of dissection and rupture, entities with extreme risk of immediate death, elective open surgery in the ascending aortic aneurysm is indicated when the diameter reaches certain limits. In order to reduce the aortic diameter, aortoplasty of reduction and aortic wrapping are acceptable surgical techniques. However, the most definitive solution is to replace the aortic aneurysm []. The patient's life expectancy in the theoretical assumption of not having the aortic aneurysm plays a key role in deciding whether it is worth operating and what type of surgical technique is preferable. Doctors and surgeons often consider that a patient's life expectancy will be recovered completely after surgery. However, replacing a part of the aorta will not prevent the rest of it from being subject to the same risk factors that caused aneurysm formation. Furthermore, due to common risk factors, patients with aortic aneurysms have a higher risk of cardiovascular events than the general population [,]. Thus, even after a successful upward aortic replacement, your life expectancy can be compromised. Therefore, any decision based on the theoretical recovery of that life expectancy can be made under false assumptions. Few studies have analysed the long-term follow-up of patients undergoing ascending aortic replacement. These studies are limited by the low number of patients [,], short follow-up [,] or high heterogeneity analyzing at the same time patients with acute aortic syndrome and elective surgery for the ascending aortic aneurysm [,].In addition, some studies [,,,,] have described the long-term survival of patients under ascending aortic surgery. But these results, without comparing them to the general population of the same territory, provide little information, as the life expectancy of any group depends on a collection of environmental and socio-economic factors of the territory where they reside. Gross domestic product, health system, eating habits or temperature are just some of the factors that have shown an impact on the life expectancy of the general population []. In this regard, there are significant differences between industrialized countries and even between the regions of the same country. For example, in 2017, the life expectancy of a 65-year-old woman was 20.6 years in the United States and 24.4 years in Japan []. Our objective was to know whether patients who substitute an ascending aortic aneurysm recover a life expectancy similar to that of the general population for the same age, sex and territory. In addition, we seek to know the late complications, the causes of death and the main risk factors in this population. 2. Experimental Section2.1. Sample and Data Collection We include all patients who were replaced electively by an ascending aortic aneurysm in our institution between 2000 and 2019. Concomitating surgery of aortic or coronary valve was allowed. Aortic valves, Bentall-Bonno procedures and all surgeries were included in the aortic root or aortic arch if the ascending aorta was also replaced. Patients were excluded if they were subjected to prior surgery in the ascending aorta or aortic root. Patients with acute aortic syndrome, chronic dissections, pseudoaneurysms or those requiring mitral valve surgery or concomitant tricuspid were also excluded. All data related to pre, intra and postoperative periods were collected retrospectively from a prospectively completed digital database by the patient's surgeon. The postoperative period was taken as the first 30 days of follow-up, or until the date of discharge of the hospital if this were beyond 30 days. Death data during follow-up were collected by one of the researchers who analyzed the information in the medical records of all health centers and hospitals in our Region. All hospitals and health centers in our region are connected intranet so that, from our institution, we can investigate all medical records and health reports. To compare the sample with the general population in line with age and sex, the death incidence tables provided by the National Statistical Institute [] were used for our region. This institute provides high-quality information on multiple country statistics. As to the incidence of death, the Institute provides information stratified by age, sex and regions of the nation. More information about the institute can be found in . 2.2. ObjectivesThe priority objectives were: (1) to compare the life expectancy and survival curves of the patients who were replaced by an aortic aneurysm ascending with that of the general population that coincides with the same age, sex and territory; (2) to compare the life expectancy and survival curves of those patients who survived the postoperative period and (3) to know their causes of death, risk factors for mortality and late complications. The secondary objectives were to compare the survival curves of these stratifying patients by bicuspid or tricuspid valve and by 70 years of age. 2.3. Statistical AnalysisThe quantitative and categorical variables are described as mean ± SD and n (%) respectively. To compare the survival of the surgical sample to the general population at play by age and sex, the following estimates were calculated: (1) observed survival; (2) expected survival and (3) relative survival (RS). The observed survival is the actual survival of the surgical sample calculated by the usual Kaplan-Meier method. The expected survival is the survival that a group of people in the general population would have if each individual was a copy of the same age, sex and region as the surgical sample. This is every individual of the general population who combines by age and sex with each individual of the surgical sample. This means that the expected survival is the survival that the surgical sample would have if they did not have the aortic aneurysm. Its calculation is performed by the Ederer II method, which is the calculation of the choice to know the expected survival of a sample []. To do this, we use information on the incidence of deaths provided by the National Statistical Institute for different ages, sex and region []. If the expected survival was included in the confidence interval of 95 per cent of the observed survival, statistical differences were not considered. RS is an estimate of the survival that the patients of the surgical sample would have in the theoretical assumption that they could only die for a problem associated with their aortic aneurysm [,]. Its calculation is made by the ratio of the observed survival rate to the expected survival rate. A 100% SR in the first year would mean that all the problems associated with the presence of an aortic aneurysm would have been completely solved with the replacement of aneurysm. However, an RS of 80% in the first year would indicate that 20% (100-80%) of patients would have died due to a problem derived or associated with the aortic aneurysm []. Therefore, if the RS confidence interval includes 100%, there is no evidence that there is mortality associated with aneurysm and suggests that the replacement has been completely effective in solving the problem []. One of the main advantages of the RS is that it allows to know mortality due exclusively to the disease in study, without knowing the causes of death []. To know the main risk factors of mortality, a Cox regression analysis was performed using as independent variables all factors that could influence the prognosis from a theoretical point of view. The proportionality of the hazard hypothesis was tested by Schoenfield's waste analysis. 95% CI was provided for the proportion of hazards (HR) and p ≤0.05 values were considered statistically significant. The variables of the model were chosen according to theoretical knowledge: age, sex, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, kidney deficiency, type of surgery (insulated replacement of the ascending aorta was the reference), chronic lung disease, extracardial arteriopathy, pulmonary hypertension, left ventricular dysfunction. All analyses were performed using STATA v.15.1 (STATA Corp, TX, USA). The observed survival, expected survival and RS were calculated automatically using the command "strs" []. Using the Ederer II method described above, this command allows, in an easy way, to match by sex and age. Ethical approval of the corresponding IRB was obtained (reference number: 20/087) Results3.1. Patients, type of surgery and postoperative results. There were 738 patients who suffered anortic upward replacement due to the aortic aneurysm. Of these, 232 (31.44%) were women and the average age was 65.27 years ± 13.09. All the characteristics of the patient are presented in . Three hundred and eighty and six patients (52.30%) were subjected to replacement of concomitant aortic valve. One hundred and forty (18.97%) were remodeled in aortic root with valve conservation. Eighty-six (11.65%) patients received an aortic replacement isolated ascendant and 30 (4.07%) individuals were subjected to ascending aorta and replacement of aortic arch. All types of surgery are described in . The diameter of the average ascending aorta was 50.93 ± 8.43 mm and 296 (40.11%) patients had a bicuspid aortic valve. Table 1 Patient Characteristics. VariableValueAge (years)65.27 ± 13.09Women232 (31.44%)Break mass index (kg/m2)28.15 ± 4.54 Surface surface area (m2)1,85 ± 0.20Hypertension 492 (66.67%)Diabetes mellitus Type 112 (1.63%)Type 265 (8.81%)Dyslipidemia 241 (32.66%)Extreme surgery28 (3.79%)Premature acute myocardial infarction 16 (2.27%) Extracardial arterypathy26 (3.53%) Creatinine cleaning 50–85 mL/min164 (22.28%)Product authentication 0.50 mL/min52 (7.07%)Chronic lung disease108 (14.63%)Central mobility 2 (0.27%)EuroScore 2 3.68 ± 3.65 EuroSCORE13.19 ± 9.86NYHA functional class: NYHA I/IV136 (18.43%)NYHA II/IV374 (50.68%)NYHA III/IV202 (27.37%)NYHA IV/IV26 (3.52%) paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (4.62%)Permanent or permanent atrial fibrillation115 (15.63%)PASP 31–55 mmHg156 (21.14%) title 55 mmHg19 (2.57%)LVEF (%) 31–50%164 (22.22%)21–30%29 (3.93%) 0.20%2 (0.27%)Grade of aortic stenosis I40 (5.42%)II29 (3.93%)III40 (5.42%)IV233 (31.57%)Aortic regurgitation Degree I74 (1.03%)II83 (11.2%)III134 (18.1%)IV232 (31.44%)Aortic valve of aorta296 (40.11%) ventricle hypertrophy 111 (15.2%)Aorta diameter (mm) Sinus of Valsalva42.77 ± 7.07Aorta ascendente50.93 ± 8.43Aortic arch40.6 ± 9.22LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; PASP: Systolic pressure of pulmonary artery; NYHA: New York Heart Association. Table 2Operation characteristics. Variable Value Intraoperative characteristics Type of SurgeryAortic valve replacement and upward aorta replacementRenovation of upward aorta rootReplacement of upward aortaReplacement of high aortaBentall-Bonno with ascending aorta replacement Aorta ascending and replacement of aortic arc (1135% aortic valve) Cardiopulmonary bypass 139 ± 60 Scots claming time112 ± 52Insurgency with circulatory detention 84 (11.38%)Use of deep hypothermia13 (15.48%)Use of moderate hypothermia with a priorgrade cerebral perfusion71 (84.52%) Concomitant coronary surgery114 (15.44%)Number of protracted tube 2675 (10.16%)28209 (28.32%)30340 (46.07%)3291 (12.33%)3421 (2.85%)362 (0.27%)EuroScore 2 3.68 ± 3.65 EurosCORE 13.19 ± 9.86 Postoperative difficulties Permanent pacemakers46 (6.23%)New atrial fibrillation144 (19.83%)Reoperation for bleeding48 (6.50%)Stroke33 (4.47%)New renal failure25 (3.38%) Medications to the high Angiotensin receptor blockers II161 (21.82%)Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors155 (20.00%)Data blockers434 (59.78%)Stats 278 (38.29%)Forty-four (5.96%) patients died during the postoperative period. Postoperative mortality for isolated ascending aortic surgery was 4 (4.65%), for the replacement of aortic valve and anortic upward replacement was 20 (5.18%) and for the replacement of concomitant aortic arch was 8 (26.67%). The cardiopulmonary bypass time was 139.25 ± 60.62 minutes and the aortic interclamation time was 112.27 ± 52.25 minutes. The average hospital stay was 10 (8–14). Causes of death, postoperative complications, and high-risk drugs are shown in and . All 144 (19.83%) patients who developed a new postoperative AF were treated with oral anticoagulants at discharge. There were 139 with vitamin K antagonists and 5 with new oral anticoagulants. Table 3 Causes of Re-operation and Death. CausaValue Causes of re-operation Aorta-related Treatment for Endovascular Therapy10 (1.36%)Aneurysm6 (0.81%)Dissection5 (0.54%)Treaty for open heart surgery Pseudoaneurysm8 (1.08%)New aneurysm2 (0.27%)Not related to aorta Endocarditis10 (1.36%)Trombosis protein2 (0.36%)Persistent aortic revival3 (0.41%)Sthetic degeneration 3 (0.41%)Myxoma2 (0.36%)Failed aortic repair7 (0.95%) Causes of death Peri-operative period n = 44 cardiogenic shock21 (2.85%) hemorrhagic shock6 (0.81%)Infection/Sepsis11 (1.49%)Other6 (0.81%)Next n = 86 (Among the survivors of the postoperative period) Cancer24 (3.46%)Heart failure18 (2.59%)Infection or sepsis10 (1.44%)Stroke6 (0.86%)A proper aortic syndrome 3 (0.43%)Sudden death3 (0.43%)Another cause22 (3.17%)3.2. Life expectancy of the full sample There were no patients lost during follow-up. The average follow-up of censored persons was 56.02 ± 36.37 months. There were 130 (17.61%) patients who died during the postoperative period and follow-up. The main causes of death were shown in . The observed survival of the sample was 1, 3, 5 and 8 years of follow-up and was 93.17% (95% CI 91,08-94,78%), 88,96% (95% CI 86,35-91,10%), 84,86% (95% CI 81.67–87,53%) and 76,53% (95%CI 71.35–80.911%). The expected survival was 1, 3, 5 and 8 years of follow-up, 97,90%, 93,30%, 88,46% and 80,39%. shows the observed and expected survival for each year of follow-up and shows the survival curves. Survival observed and expected for the entire sample. Table 4 Cumulative survival of the sample and the reference population. The annual relative survival for the entire sample is also described. 95.95% – 95.95% (IC95%) 95.95% (IC95%) 95.95% (CI 95%,98%) This is not a cumulative estimate. The RS during the first year of follow-up showed a mortality ratio due to the aneurysm RS = 95.02% (CI 95% 92.82–96.71 per cent). The RS of the rest of the follow-up did not show excess mortality due to the disease, or what is the same, the expected survival was similar to the observed survival. and display the RS for calculated interval for each year of follow-up. Relative survival for each year of follow-up.3.3. Life expectancy for patients who survived the postoperative periodAmong the 694 patients (94.04%) who survived the postoperative period, 86 (12.39%) died. Its cumulative survival observed at 1, 3, 5 and 8 years of follow-up was 98.29% (95% CI 96.85–98.97%), 94.07% (95% CI 91.87–95.70%), 89.9% (95% CI 86.92–92.33%) and 82.72% (95% CI 77.68–86.71 %). The expected survival in 1, 3, 5 and 8 years of follow-up was 97.91%, 93.22%, 88.30% and 80.27%. shows the accumulated survival for the sample and reference population. shows the survival curves. Survival observed and expected for patients who survived the postoperative period. Table 5 Cumulative survival of the sample and the reference population. The annual relative survival is also described. Data for survivors of the postoperative period. 95.94% (IC95%) 95.94% (IC99%) 95.94% (IC91%) 95.94% (IC99%) This is not a cumulative estimate. The first-year specific RS did not show an excess of mortality due to aneurysm, 100.30% (CI 95% 98.92-101.09%). The rest of the calculated RS for each year of follow-up showed no mortality due to aneurysm, or what is the same, the expected and observed mortality was similar. shows the RS per interval for each of the years of follow-up. The sample survival curves and the general population stratified by bicusspid or tricusspid valves and by age of 70 are shown in and , respectively. Bicuspid or tricuspid aortic valve stratified survival curves for patients who survived the postoperative period. Survival curves stratified by age or 3.4. Causes of Death During follow-up, risk factors and late complicationsIn 718 patients (97.29 per cent), the aorta did not require a second intervention. There were 20 patients who were undergoing surgery by the aorta and 10 (1.36%) of them had endovascular surgery to treat another aneurysm in the descending aorta and 10 (1.36%) patients required open aortic surgery. For eight of them, it was due to pseudoaneurisma and for two it was due to the presence of a new aneurysm in the aortic root. Thirty patients required heart surgery for other circumstances. The causes of re-operation are available in . After the Cox regression analysis, the following risk factors of mortality were identified during follow-up: age (HR = 1.03 CI 95% 1.01–1.05; p = 0.002); two types of surgery, concomitant replacement of the aortic arc (HR = 4.95 CI 95% 1.94HR–12.60; p = .001) and concomitant replacement of the arctic 6 arural arural arural ar VariableHR95% CIp ValueWomen0.770.51–1.210.29Age1.031.01–1.050.002 Type of surgery Aortic valve replacement and aortic aorta replacement1,620.86–3.030.14 aortic root remodeling with an ascending aorta replacement.190.49–2.860.74Coupon repairs with aortic aortic aortax1.930.81–4.760.14Aortment and replacement of aortic arc4.951.94–12.60 Creatinine cleaning 50–85 mL/min1.390.90–2.170.14Creative demining Diabetes Type-20.890.45–1.720.85Type-12.220.98–5.140.06Extracardiac arteriopathy0.330.08–1.370.13 disease1.20.74–1.950.46PASP 31–55 mmHg0.990.25–4.120.99 confidence55 mmHg1.210.78–1.880.39LVEF (%) 31–50%0.880.55–1.420.6121–30%1.090.39–3.060.86CI: Confidence interval; Human resources: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. PAP: Pulmonary systolic blood pressure. Among the 86 patients who died during follow-up, cancer was the cause of death in 24 patients (27.90%), heart failure in 18 (20.93 per cent) and the aorta only caused 2 confirmed deaths (2.32 per cent) taking into account that 2 patients (2.32 per cent) died of sudden death without autopsy. All causes of death are presented in .4. Debate Since the life expectancy of a population is greatly influenced by the geographical region where it lives, we compare the life expectancy of patients who suffered an aortic upward replacement with that of the general population of the same region corresponded to age and sex. In addition, this study first used the RS to know if these patients recovered their life expectancy after the operation. This method, common in studies on cancer therapies [,], has recently been used in the cardiovascular field [] and allows us to calculate the risk of mortality due to the disease without knowing the causes of death []. Our main finding was that the life expectancy of patients who were replaced by an ascending aortic aneurysm and survived the postoperative period was similar to that of the general population. Analyzing the entire sample, that is, patients who died during the postoperative period, patients who replaced the ascending aorta did not achieve a life expectancy similar to that of the general population. This could be inferred from the lack of overlap of ITC of the survival curve observed with the expected survival curve. Thus, the probability of survival was lower in the surgical group than in the general population in the first six years and then it was equated between the two groups from the beginning of the sixth year, remaining equal until the eighth year. This occurred because the RS, which is an estimate of the excess mortality due to the disease (or associated conditions such as surgery), was not the same throughout the follow-up period. The RS indicated an excess of mortality due to aorta of 5% (100–95.02%) during the first year. Beyond this first year, relative survival did not identify excess mortality due to aorta in the rest of the follow-up. This was caused by perioperative mortality of almost 6%, which had a negative effect on survival in the surgical group. This postoperative mortality observed was higher than that expected by EuroSCORE II (3.68%) but lower than that predicted by the logistic EuroSCORE (13.19%). The surgeries performed 20 years ago, when the operating mortality was greater, can explain. In the group of patients who survived the postoperative period, the survival curve was practically identical to that of the general population during the entire follow-up period. The RS per year of follow-up did not identify any year with an excess of mortality due to the disease indicating that the operation completely recovered its life expectancy. With perioperative mortality for the aortic upward substitution isolated from less than 1% reported in some recent studies [,], this finding gives an incredibly promising scenario from which we can infer that the aneurysm of the ascending aorta is today a condition that does not have to affect long-term survival. In addition, the risk of a late complication associated with aorta was very low (only 3 patients, 0.43%) indicating that aorta is no longer a problem in these patients. On the contrary, cancer and heart failure are the main causes of death during follow-up, which reinforces the hypothesis that the aorta problem is solved. Therefore, risk factors for the formation of aneurysms such as hypertension or dyslipidemia were not strong enough to reduce life expectancy in these patients, which could be explained by rigorous clinical follow-up after surgery and throughout their lives. In short, patients with an ascending aortic aneurysm may be informed that they undergo elective surgery to replace it and survive the postoperative period that their life expectancy will be fully recovered. Such life expectancy can be easily consulted in the relevant national statistics. This study has some limitations. First, it is subject to possible partialities derived from its retrospective character. Second, not all variables with a possible impact on the final results could be studied. Intraoperative or postoperative transfusion are examples. 5. ConclusionsThe long-term survival of patients undergoing elective surgery for the ascending aortic aneurysm is totally conditioned by operational mortality. Those who survive the post-operative period fully recover their life expectancy, which can be consulted in the relevant national statistics. Supplementary materials The following are available online in .Author ContributionsConception and design: D.H.-V, I.P., C.M.; Data extraction: A.E., R.D.; Analysis and interpretation: D.H.-V., C.M., R.A.; Writing (project and final): P.A., J.S., D. All authors have read and agreed on the published version of the manuscript. Conflict of interest The authors do not declare a conflict of interest. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Warning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. Quality of life after the replacement of the ascending aorta in patients with true aneurysmsAbstract The true aneurysms of the ascending aorta often remain undetected, but their sequel carries a high rate of mortality and morbidity. The operating risk of non-emergency replacement of the ascending aorta is low. It is important to consider the quality of life to determine the most appropriate treatment for patients who have aneurysms but who have not yet experienced major complications. From January 1999 to December 2003, 134 consecutive patients were replaced by a dilated upward aorta in our center. A further 124 patients with acute or chronic aortic dissections, aortic breakdown or intramural hematoma were excluded. Standard SF-36 and general health questionnaires were sent to the 124 survivors who could be traced. The follow-up was 98.4% complete. The average age of the survivors was 61.7±11 years, and 63.4% were men. The operating procedures consisted of the supracoronary substitution of the ascending aorta by 35.9%, the wheat procedure by 44%, the David procedure by 11.2%, the Bentall-DeBono procedure by 9%, and the Cabrol procedure by 2.2%. Patients were monitored until May 2005. The mortality rates of 30 days and half of the period were 3.7% and 3.9% respectively. Morbidity due to stroke was 6%, 6% bleeding and 4.4% myocardial infarction. The postoperative evaluation of quality of life revealed many SF-36 subscales that were below the norm compared to a standard population in physically dominated categories. Replacement of the toothed ascending aorta carries an acceptable risk in relation to operational death and postoperative quality of life, although the latter showed a certain decrease compared to the quality of life in a normal and healthy population. Aneurysms of the ascending aorta are considered to be a serious disease, especially in older patients, because the operating risk is generally greater due to concomitant diseases. When not treated, aneurysms have a high mortality rate; often they remain undiscovered until dissection or rupture. To avoid these sequelae, early diagnosis is essential. The data of many studies on the progression of aneurysms show that the risk of operation is justifiable in the light of the probability of lethal sequel to chronic asymptomatic disease. Once an aneurysm reaches a maximum diameter of 6 cm, the annual probability of rupture, dissection or death is 14.1%. Apart from morbidity and mortality rates, which are widely published, there is little information about the quality of life among patients who have undergone major aortic surgery before dissection or rupture. However, quality of life is also an important consideration in assessing the success of the operation, especially in patients whose aneurysms were not symptomatic before the surgery. This study analyzes the operational result and quality of life of patients who have had the replaced ascending aorta, compared to the quality of life of the German population in general. Patients and Methods From January 1999 to December 2003, 134 consecutive patients received a replacement of the toothed up aorta in our center. This study excluded 124 patients with acute or chronic aortic dissection, rupture or intramural hematoma, either through preoperative studies or through intraoperative findings. We include patients who were subjected to additional coronary bypass grafts (CABG) or valve procedures. There were 85 men and 49 women, whose average age was 61.7 ± 11 years (range, 25–80 yr). There were 4 patients with Marfan syndrome (3%). In 1 case, an infection with Treponema pallidum was confirmed as a cause of aneurysm. It describes the cardiovascular risk profile of patients enrolled in the study. TABLE I. Cardiovascular risk factors in all 134 Patients with true aneurysm of the ascending aortaThe 14 cases (10.4%) were reoperatives. The concomitating procedures included the replacement of aortic valve in 71 patients (53%), CABG in 30 patients (22.4%), mitral valve repair in 6 patients (4.5%), aortic bow replacement in 4 patients (3%), atrial septal defect closure in 2 patients (1.5%), and myectomyectomy for hypertrophic heart disease together with a head fistula closure in 1 patient (08%). The operation was classified as elective in 129 patients (96.3%), emerging in 1 patient (0.8%), and urgent in 4 patients (3%). When classified as urgent or emerging, the main indications for surgery were severe valve dysfunction, atrial fistula or coronary heart disease. Patients with concomitant CABG presented significantly higher ASA scores (American Society of Anesthesiologists) than the rest of the group (3.3 ± 0.5 vs 3.0 ± 0.6; P = .04). The main indications for heart surgery are shown in . An aneurysm of the ascending aorta was not the main indication for cardiovascular surgery in all cases. In 26 of 134 cases (26.1%), a true aneurysm of the ascending aorta was the main surgical problem; and often the main diagnosis before the operation was the dysfunction of the aortic valve, coronary stenosis or both. TABLE II. Preoperative Indication for Cardiac Surgery among the 134 Patients in Our Study GroupPerformative Procedures () consisted in supracoronary substitution of the ascending aorta in 33.6% of patients, Trigo procedure (substitution of the ascending aorta and the aortic valve) in 44%, David procedure (substitution of the ascending direct aorta with reimplantation III. Operative technique used to replace the ascending aorta in 134 patients The average operating time was 295,5 ± 99 min. Myocardial protection was achieved in all patients with antegraded administration of cold-glazed cardioplegic solution (Berschneider resolution, 30 mL/kg bw, Dr. F. Koehler Chemie; Alsbach-Haehnlein, Germany). Operating time was significantly longer for patients who had undergone previous cardiac surgery (399.1 ± 172.2 min vs 283.4 ± 79.4 min; P = 0.03). In 65 patients (48.5%), the native aortic valve was replaced, and in 6 patients (4.5%), an aortic valve prosthesis was replaced. In 30 patients (22.4%), concomitant CABG was performed. The Short-Form-36 questionnaire (SF-36), a tool for the assessment of 8 dimensions of health-related quality of life, has been validated for its application to the German population. The internal consistency (Cronbach α) of SF-36 subscales varied from 0.57 to 0.94. The 134 patients survived the operation and were discharged from the hospital. At the time of the study in 2004-2005, 10 patients had died of causes that could not be determined. Standard SF-36 and general health questionnaires were sent to 124 survivors. The follow-up was 98.4% (122/124) complete. A further 10 patients (7.5%) died during the follow-up period; 2 patients did not participate for personal reasons. The average follow-up time was 36.4 ± 15.5 months (range, 11–58 m). In comparison with the results of the SF-36, standard values of the 1998 Bundes-Gesundheits Survey were used. These standard values are consistent with age, sex and nationality. Statistical Analysis All pre, intra and postoperative data were collected in an Access database (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Wash). Continuous data were analyzed using the t-test of the unpaid student, and categorical data were analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Values were expressed on average ± SD. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software package (Version 11.5 for Windows, SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Ill). SF-36 subscales were analyzed using scripts provided by Hogrefe (Hogrefe Verlang; Goettingen, Germany). ResultsDuring their hospital stays, 8 patients (6%) received at least 1 additional operating intervention (for bleeding, to cite 1 example). Postoperative sequelae are summarized in .Table IV. Severe postoperative complications after the replacement of the ascending Aorta The 30-day mortality rate was 3.7% (5/134). Half-term mortality (up to 5 yr) was 3.9% (5/129). The average time for death was 396.3 ± 529.9 days (range, 8–1, 405 d). The causes of death are described in . TABLE V. Causes of death after substitution of the ascending aorta There was a very significant connection between the previous cardiac operation and postoperative death (P = 0.001). Four of the 14 patients (42.9 per cent) who had been subjected to previous cardiac surgery died in May 2005, compared to 6 of 114 patients (5.3 per cent) who had not been subjected to prior surgery. Neither concomitant bypass surgery nor any other specific operating procedure, including the Cabrol procedure, was associated with a higher postoperative mortality rate. There was a statistically significant association between death and postoperative myocardial infarction (Table P VI. Peroperative compositions with statistically significant influence on postoperative deathThe analysis of the questionnaires revealed that 55.7% (68/122) had no discomfort until the time of the primary diagnosis. There was a postoperative reduction of dyspnea (P = 0.10) and chest pain (P = 0.02), compared to the preoperative state. Before the operation, 57 of 122 of the patients surveyed continued to participate in their professional life. Subsequently, 22.8 per cent of the (13/57) had to reduce their working time, and another 31.6 per cent (18/57) of the patients had to give up their work. The evaluation of completed SF-36 questionnaires showed heterogeneous results, which varied with the age group. In general, the values of many subscales were found below the reference values of the Bundes-Gesundheits Survey (), although there were large deviations between age groups. The results for 2 age groups are presented and .Fig. 1 Postoperative quality of life versus quality of life in the German standard populationBP = body pain; GH = general health; ERF = emotional function; f = woman; m = man; MH = mental health; PF = physical functioning; PF = physical functioning; SF = social functioning; SF-36 = Short Form-36 Questionnaire; VIT = vital 2 3 Postoperative quality of life versus quality of life in the standard German population: ages from 70 to 79 yearsBP = body pain; GH = general health; ERF = emotional function; f = woman; m = man; MH = mental health; PF = physical functioning; PRF = physical functioning; SF = social functioning; SF-36 = Questionnaire of the physical form - 36; VIT = vitality The values for physical pain were above normal values for almost all age groups and for both sexes. There were no results consistent with the values reached from social and mental subscales for different subgroups. Depending on age and sex, the results were higher or lower than the standards. There was little decrease in general health from 12 months to more than 60 months after the operation, regardless of age group. In cases where the substitution of the ascending aorta had occurred less than a year earlier, patients experienced an improvement in health compared to the previous year, and a low preoperative value for general health was linked with an increase in overall health. These facts should be evaluated in the light of the concomitant diseases and the average age (64.4 yr) of the patient population (). Fig. 4 Health changes for 60 months postoperative and beyond. *A higher value indicates a worsening health since the previous year. The different operating techniques did not have statistically significant influence on postoperative quality of life. However, concomitant bypass surgery lost the level of significance by a slight margin (P = 0.09). The extended stay in the hospital was significantly linked with a postoperative loss of quality of life (P = 0.04). Other values with a potential influence on quality of life are presented in .Table VII. The influence of adverse factors on postoperative quality of life after the substitution of the ascending aorta in 134 patients Operational therapy in application to true aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections is similar. However, operating death and morbidity rates differ significantly. Most real aneurysms do not cause any symptoms for a long time and are operated on an elective basis, while dissections occur sharply and operate on an emerging basis. The main complications for acute aortic dissections are trazo, renal and mesenteric ischemia and cardigen shock. However, many studies do not clearly distinguish between true aneurysm and dissection. They tend to focus more on operational techniques than on underlying diseases. In addition, attempts to compare the operating results in medical literature are often difficult, because there is great variability among older patients, concomitant diseases, genetic background and previous operations. Study groups with a high proportion of Marfan syndrome tend to have better operating results, as these patients are usually significantly younger than patients with aortic aneurysms related to the sporadic or not Marfan and do not have concomitant coronary disease. This study was created not only to evaluate the operational results, but also to investigate the quality of life after elective operations of true aneurysms of the ascending aorta. We include all patients who were subjected to surgery for the true ascending aortic aneurysm, regardless of the underlying disease. We expressly included patients who were undergoing concomitant heart surgery. In many of these cases, the aneurysm of the ascending aorta was not the main indication for surgery. The 30-day mortality rate of 3.7% in our group was comparable to that of other studies, ranging from 1.8% to 17.9%. Operating death in populations with a high proportion of cardiac reoperatives ranges from 8.6 to 17.9 per cent, while primary operations have a lower rate of early mortality from 1.8 per cent to 8.6 per cent after prosthetic replacement. Because 10.5 per cent of our patients were re-operated, our operational mortality rate seems to be consistent with the mortality rates reported above. In our series, the choice of operating procedure did not have the significant statistical impact on postoperative survival that other authors have described. The exception in our study was the Cabrol procedure, which had a high early death rate: 1 patient of 3 died (33%). Possibly this was the result of the small number. This technique has been informed that it has worse results than other procedures and should be applied only if there is no other option. To date, little is known about the quality of postoperative life after the substitution of the ascending aorta in patients with true aneurysms. Belov and Karaeva showed that the quality of life increased in many subscale values of SF-36 after the prosthesis replacement of the ascending aorta. The SF-36 is a well-established instrument, in a variety of disciplines, to measure the quality of life, and of course is not specific to 1 disease. The interpretation of postoperative quality of life in patients with true aneurysms is difficult, because the aortic torachic aneurysms are in most cases asymptomatic before surgery; the quality of preoperative life, although not proven, is probably normal. Although Olsson and Thelin found that postoperative quality of life was reduced after chest aorta surgery, postoperative quality of life in patients with aneurysm may be influenced more by concomitant diseases than by the operation itself. Among these studies, there are no consistent results in quality of life after the prosthesis replacement of the ascending aorta, and this is also true of our results. Other explanations for this inconsistency can be found in the wide distribution of age in our study and, in particular, in the presence of concomitating diseases such as coronary disease, which are linked to a higher risk of perioperative complications. Comparison of quality of life requires a population of control of age and sex. Our control population was provided by the Bundes-Gesundheits Survey, which provides standard values for the German people. Among the members of our study group, we find that the functional class of the New York Heart Association was not significantly improved, while the Canadian Cardiovascular Society class was. In particular, physical pain — an essential measure of quality of life — was reduced in our patients, although the original pain probably did not arise from the aneurysm itself, but from coronary disease or from the dysfunction of the heart valve. Undoubtedly, concomitant diseases contributed to our finding that many patients had to reduce their working time after aortic replacement, or even to withdraw from professional life. Even so, this finding shows that chest surgery itself, which carries complications such as stroke, can have a great impact on quality of life. We also find that prolonged stay in the hospital, an additional effect of a complicated perioperative course, led to a worse quality of life. Reducing perioperative complications in modern heart surgery can be a key to improving postoperative life quality. However, heart surgery in general (with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass) did not seem to give a great improvement in quality of life, compared to aortic surgery in particular. Limitations This study was designed to evaluate data retrospectively, excluding comparison of pre and postoperative SF-36 scores. However, medical literature does not say anything about the diminished quality of life among unoperated patients living with asymptomatic aortic aneurysms, which strengthens the likelihood that the poorer quality of life among the patients operated is an operational effect. Conclusions Although patients with true aneurysms of the ascending aorta are often asymptomatic, they are not healthy. Once the aneurysm reaches a diameter of more than 5 cm (regardless of the cause), these patients live with a high risk of death resulting from acute dissection or rupture. Our study of operational results and postoperative quality of life indicates that invasive intervention can be performed with good results in the mid-term and acceptable quality of life. Footnotes Page Address Reprint: Christoph Schmitz, MD, Department of Cardiac Surgery, University of Munich, Marchioninistr. 15, 81377 Munich, Germany. E-mail: ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Ascending Aortic Aneurysm: Repair, Surgery, and Size Criteria

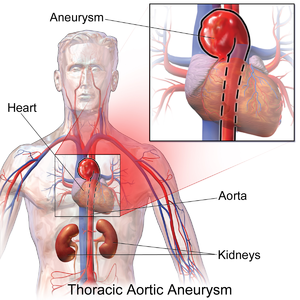

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm | Frankel Cardiovascular Center | Michigan Medicine

Aortic Aneurysm Surgery | Columbia University Department of Surgery

Yearly rates of adverse events related to ascending aortic aneurysm... | Download Scientific Diagram

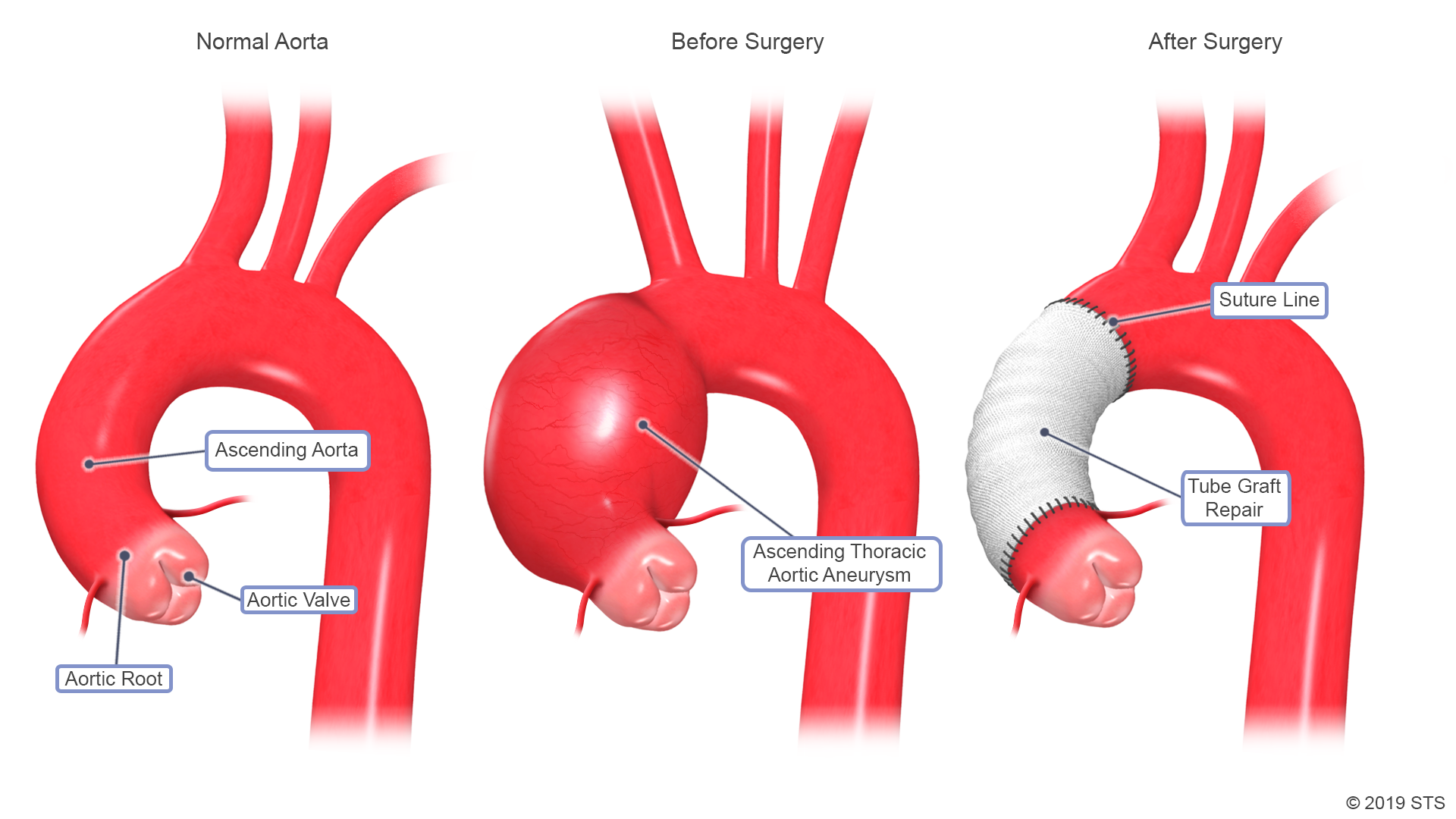

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Surgery

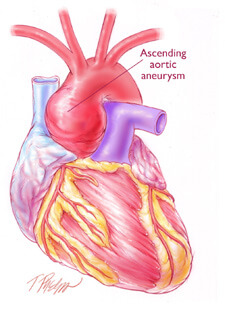

Aortic Aneurysms | Dr Krasopoulos

Average annual growth rate of the ascending aorta based on initial... | Download Scientific Diagram

Ascending Aortic Replacement | Main Line Health | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Distribution of maximal ascending aortic size of the patients before an... | Download Scientific Diagram

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Surgery

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm | Frankel Cardiovascular Center | Michigan Medicine

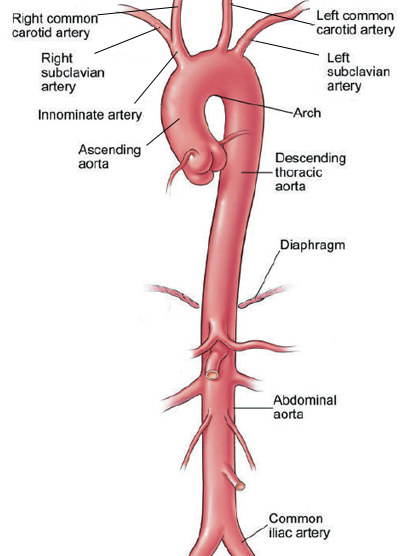

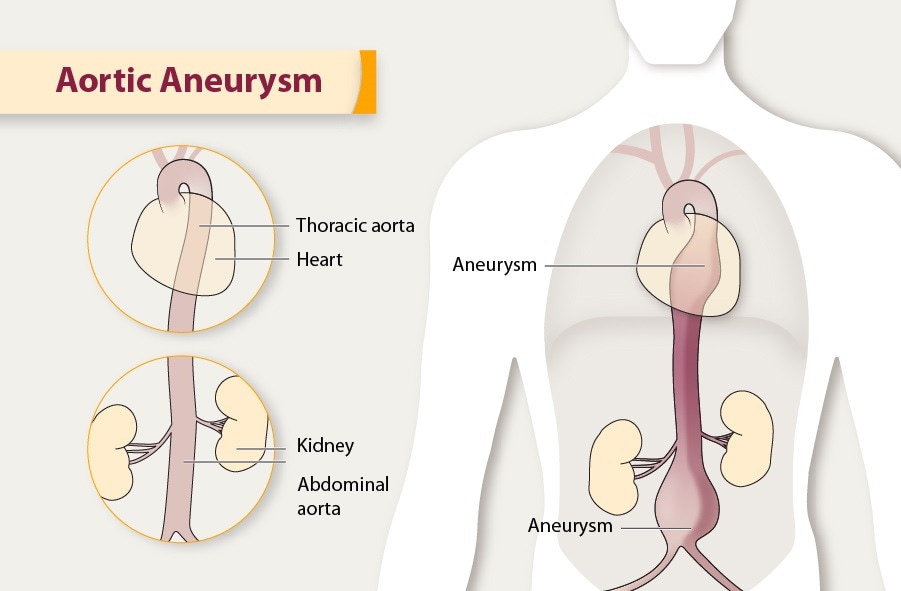

Thoracic and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms | Circulation

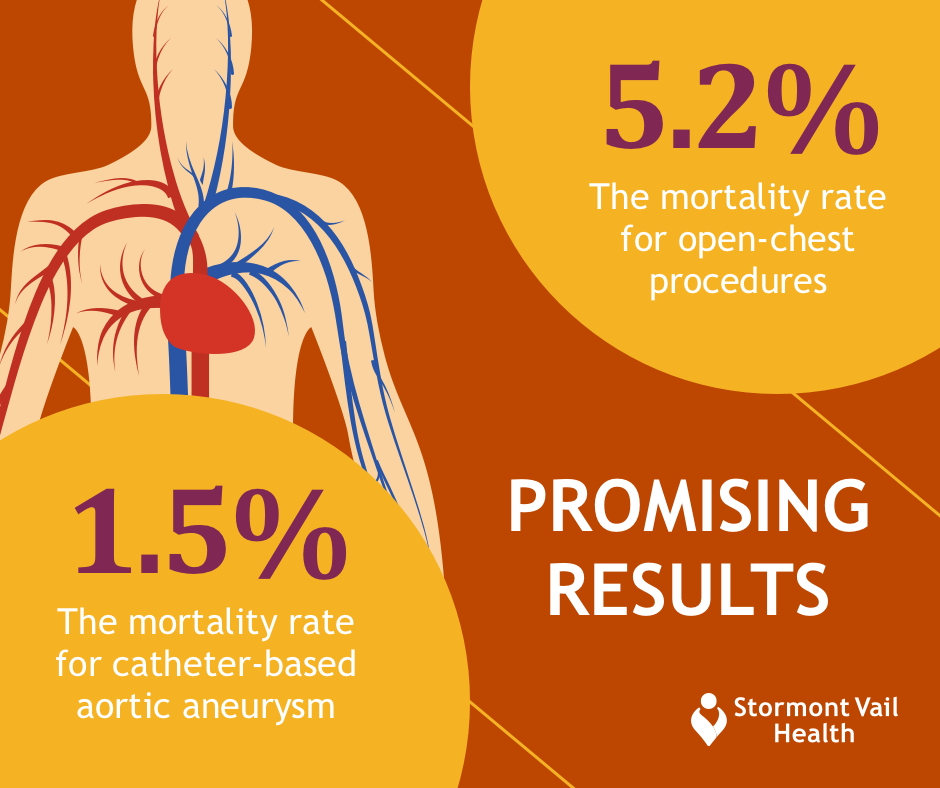

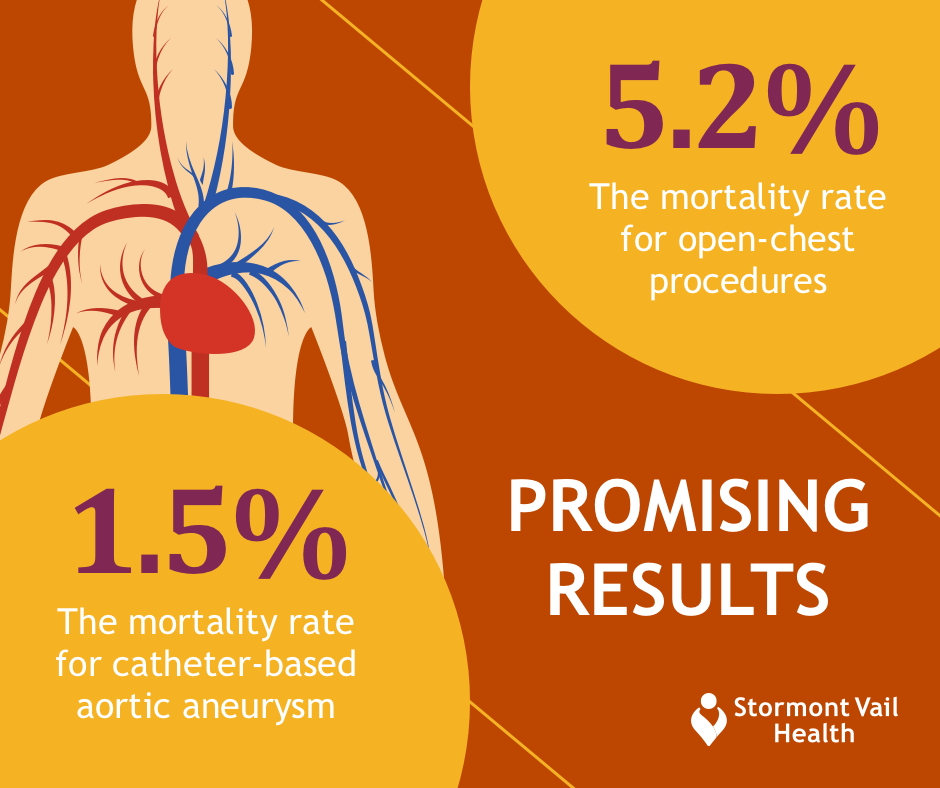

Aortic Aneurysm Repair: Is Catheter-Based Treatment Right for You? - Stormont Vail Health

emDOCs.net – Emergency Medicine EducationThoracic Aortic Aneurysms: Pearls and Pitfalls - emDOCs.net - Emergency Medicine Education

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm | The Patient Guide to Heart, Lung, and Esophageal Surgery

Thoracic and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms | Circulation

Decision-making algorithm for ascending aortic aneurysm: Effectiveness in clinical application? - The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA): Treatment by the Best Surgeons | University of Utah Health

Thoracic aortic aneurysm - Wikipedia

Aortic Aneurysms | Dr Krasopoulos

The Role of Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR) of Thoracic Aortic Diseases in Patients with Connective Tissue Disorders - A Literature Review

Reoperative Repair of Aortic Root and Ascending Aorta - Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery

Aortic Aneurysm Surgery

Height alone, rather than body surface area, suffices for risk estimation in ascending aortic aneurysm - ScienceDirect

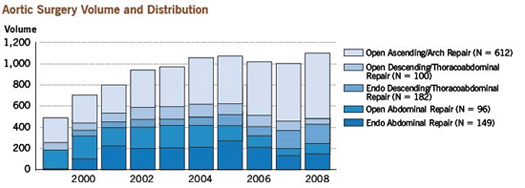

Surgery on the Aorta - First National Adult Cardiac Surgical Database Report - NCBI Bookshelf

Aortic aneurysm | Leaders in Pharmaceutical Business Intelligence (LPBI) Group

Surgical treatment of the dilated ascending aorta: when and how? - The Annals of Thoracic Surgery

Ascending aortic aneurysm

Ascending aortic aneurysm: Symptoms, causes, and types

Gender-Specific Differences in Outcome of Ascending Aortic Aneurysm Surgery

Risk of Rupture or Dissection in Descending Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm | Circulation

RACGP - Aortic aneurysms – screening, surveillance and referral

Aortic Aneurysm | cdc.gov

Decision-making algorithm for ascending aortic aneurysm: Effectiveness in clinical application? - The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery

Thoracic aortic aneurysm - Cancer Therapy Advisor

31 Aortic aneurysm ideas | aortic aneurysm, aneurysm, thoracic

Yearly rupture or dissection rates for thoracic aortic aneurysms: simple prediction based on size - The Annals of Thoracic Surgery

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection - ScienceDirect

Thoracic aortic aneurysm: How to counsel, when to refer | Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms - Heart and Blood Vessel Disorders - MSD Manual Consumer Version

Ascending Aortic Aneurysm: Repair, Surgery, and Size Criteria

Ascending Aortic Aneurysm: Repair, Surgery, and Size Criteria

Posting Komentar untuk "ascending aortic aneurysm surgery success rate"